Study shows that an approximation among the BRICS countries results in fruitful science

article in portughese published at Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

Jan 21

article in portughese published at Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

Jan 13

The Chronicle of Higher Education

January 13th, 2015

By Karin Fischer

In proposing to make community college free for millions of Americans, President Obama would buck global trends.

Over the last two decades, almost every country that has taken up tuition policy has moved to charge fees, not to rescind them. Most notably, universities in Britain, which were free until the late 1990s, have nearly tripled their tuition fees in recent years.

“Most of the globe is moving toward, not away, from tuition,” says D. Bruce Johnstone, a professor emeritus at the State University of New York’s University at Buffalo and an expert in comparative higher education.

The result is a bipolar world, split between countries that expect students to cover at least some of the cost of their education and those that believe that a college degree should be paid from national coffers. Put another way, it is a divide between societies that see higher education as a mostly private benefit and those that view it as a public good.

While their number is shrinking, in the countries without tuition, the notion of free higher education often resonates strongly with citizens, suggesting that Mr. Obama’s proposal could also find popular backing in the United States.

Take Germany. After a constitutional court in that country ruled in 2005 that universities could charge tuition, about one-third of German states, which have primary oversight of higher-education institutions there, adopted modest fees, typically about 1,000 euros, or about $1,200. But in the decade since, each and every state has moved to roll back tuition.

The reversal was the result of political pressure, says Rolf Hoffman, executive director of the German-American Fulbright Commission. “Germans would sooner pay for kindergarten—and they do—than pay for university,” Mr. Hoffman says. “They feel very strongly that it’s an unalienable right to have access to higher education.”

Nina Lemmens, who heads the German Academic Exchange Service’s New York office, says the attitude toward higher education in Germany is different than that in the United States, where students and families have been asked to shoulder an increasingly larger burden of paying for a college degree. In Germany, covering the cost of education is seen as “an investment in the people,” she says, “and for the good of the whole society.”

Germany isn’t alone. Austria, too, imposed, then abolished, tuition, despite threats to public financing there. Mexico “almost had a revolution” over moderate tuition increases at its public universities a decade ago, says Philip G. Altbach, research professor and director of the Center for International Higher Education at Boston College.

Denied tuition revenue, Mexican universities have been unable to grow, leaving many students to turn to private institutions.

Indeed, offering higher-education programs at no cost sometimes leads to situations in which problems like social inequality are actually exacerbated by the fees policy rather than ameliorated.

In Brazil, where public universities remain free, 75 percent of students attend private colleges. Spots at the country’s public institutions are highly competitive, creating an “inversion in the higher-education system,” says Marcelo Knobel, a professor and former dean of undergraduate education at the University of Campinas. Students from wealthier backgrounds tend to score better on university-entrance examinations. Thus, the students “who can get in are those who could afford to pay,” he says.

A new affirmative-action policy, to be rolled out over the next several years, will set aside more seats at Brazilian universities for minority and low-income students and those who attended public high schools.

Globally, there’s little evidence that low or no tuition guarantees broader access to a college education—the stated goal of Mr. Obama’s plan. Indeed, a 2005 comparative study of 15 countries found that access to higher education was not necessarily directly linked to the affordability of a college degree. And some of the countries with the fastest-growing college-going rates today are in Asia, where students and families generally foot the bill.

“Access is as much related to capacity and to the lack of quality options as to price,” says Alex Usher, a Canadian higher-education consultant and the study’s author. Countries with high tuition but generous student-loan programs may also have higher university-enrollment rates than those without tuition, a second report, published in 2012 by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, concluded.

Still, Mr. Usher cautions that the distinctiveness of the American higher-education system (few nations have anything similar to community colleges, for example) and of the president’s proposal (specifically aimed at institutions that enroll the lowest-income students) may make it hard to draw inferences from other countries’ experience.

Even so, observers of Mr. Obama’s plan may want to keep their eye on one other country, Chile. After sometimes-violent student protests, that nation’s president, Michelle Bachelet, made free tuition a major plank of her 2013 re-election campaign.

Like the American proposal, however, its enactment is far from certain.

Dec 26

See recent article on Access to Higher Education in Brazil, published in the Journal Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning

Dec 07

I will discuss a rather delicate issue that is now happening in the state of São Paulo that, in my opinion, puts at risk the huge effort made in the last 50-60 years to build an excellent public university system. The topic is complex because it is related to salaries, and, in a country with enormous inequalities, it can be risky, even considered politically incorrect, to discuss salaries of university professors who have contributed more than 30 years of public service. However, I will try to show the situation and the current problem that is causing a lot of discussion and controversies.

The University system in Brazil is composed of public (federal, state and municipal) and private (for profit and non-for-profit) universities. The municipal system is very small, and the federal system is very centralized. All salaries for staff and faculty members are exactly the same for equivalent levels. However, different tracks of each public servant can lead to different salaries over time, depending on their administrative duties, number of years at different levels, external projects, etc. There is a maximum value for the salaries (the so-called “teto” or “ceiling”), which corresponds to the salary of the Ministries of the Supreme Court (in 2014 this is R$ 29.462,25, and will increase to R$ 30.935,36 in 2015, effectively US$ 11,500 per month).

Since 2003 the states can choose to set the “ceiling” for state public servants at 90.25% of the salary of the Ministry of the Supreme Court (today, R$ 26.589,25) or the salary of the Governor of the State. Nowadays, 17 out of 27 States have chosen to have the maximum wage related to the Ministry of Supreme Court. However, the state of São Paulo and nine other states have chosen to tie salaries to the compensation of their governors. As expected, as all the public servants salaries are indexed to that of the Governor, this value can be politically adjusted to prevent an increase of state expenditures.. It is also opens the door to populist-oriented policy, considering that in truth the Governor has so many additional non-monetary benefits (housing, driver, meals, etc..) that he/she doesn´t really depends of the monthly salary to live.

In the state of São Paulo the salary of the Governor is currently R$ R$ 20.,662.00 (around US$ 8,000/mo). To this gross salary, one should deduct several taxes, that add up to around 38%. Thus, the maximum net salary in the state of São Paulo is about US$ 5,000.00 per month, which leads to annual net stipend of around US$ 67,000.00 (based on 13 payments made each year in Brazil). This represents the maximum salary allowed for full professors and senior administrative staff after 20-30 years of dedication to the university.

Evidently, this discussion can be considered politically incorrect in a country where the minimum wage is R$ 724.00 (US$ 280/mo), and the average salary is below R$ 2,100.00 (US$ 800/mo). A gross salary of more than R$ 20,000.00 is considered to be at the top quintile (indeed, with more than R$ 10,000 above the value to be considered as class A, i.e., R$ 10,860.00, in the socio-economic classification). On the other hand, we are talking about the difficult and important development of high quality universities in a developing country. The current parity among the universities and the limit on salaries, hinders the possibility of attracting the best young talent needed to support the development of this rather young university system.

The expected time bomb has been postponed during the last 10 years, because there was a legal issue related to the interpretation of the 2003 law. However, in the last few month the Supreme Court finally decided that all salaries (including those extra incentives that pre-dated the 2003 law) must be restricted to the state-defined limit. Furthermore, the more recent law of transparency passed in 2011, was applied by one of the main Brazilian newspapers (Folha de São Paulo) to force the University of São Paulo (USP) to publish the salaries of all its staff and faculty (see article). This has generated a rather interesting debate in the last few days, regarding complex issues of law, transparency, and the economic crisis, among others. In the short term, it is expected that a rather large number of faculty and staff members who qualify for retirement, will proceed with it, once their salary is reduced. In addition, it will be difficult to find senior faculty willing to occupy administrative positions, such as department chair, undergraduate coordinator, etc., without the award of extra stipends.

Finally, it is important also to consider the important issue the attraction of talent, which is fundamental for the future quality of the research, teaching and services provided by the university, and to keep pace with a globalized world. How can the State Universities of the State of São Paulo maintain their current successful trajectory of development if they will not be able to attract and maintain the best talent? Limiting salaries at the top of the career ladder to a rather low value (compared to the market and to the global higher education setting) for political reasons will certainly damage a university system that has been built with concerted effort, that is considered to be among the best in Latin America, and that has a fundamental role in the development of Brazil.

See the original post at “The World View” – Inside Higher Education

Nov 30

Strange Matter Green Earth is a new pioneering educational venture developed by the Materials Research Society. It is an international traveling materials science exhibition that will enable millions of people across the globe to explore ways in which advances in materials can lead to a more sustainable future. Visitors will discover the story of the co-evolution of man and materials, and learn how materials, the stuff of history, will meet the needs of the present without compromising future generations to meet their own needs.

Building on the incredible success of the MRS Strange Matter traveling exhibition, Strange Matter Green Earth aims to empower the world’s citizens to make sustainable choices in their own lives and communities.

To learn more, check the Strange Matter Green Earth web site.

See also the video.

Oct 30

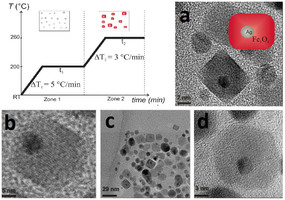

A temperature pause introduced in a simple single-step thermal decomposition of iron, with the presence of silver seeds formed in the same reaction mixture, gives rise to novel compact heterostructures: brick-like Ag@Fe3O4 core-shell nanoparticles. This novel method is relatively easy to implement, and could contribute to overcome the challenge of obtaining a multifunctional heteroparticle in which a noble metal is surrounded by magnetite. Structural analyses of the samples show 4 nm silver nanoparticles wrapped within compact cubic external structures of Fe oxide, with curious rectangular shape. The magnetic properties indicate a near superparamagnetic like behavior with a weak hysteresis at room temperature. The value of the anisotropy involved makes these particles candidates to potential applications in nanomedicine.

A temperature pause introduced in a simple single-step thermal decomposition of iron, with the presence of silver seeds formed in the same reaction mixture, gives rise to novel compact heterostructures: brick-like Ag@Fe3O4 core-shell nanoparticles. This novel method is relatively easy to implement, and could contribute to overcome the challenge of obtaining a multifunctional heteroparticle in which a noble metal is surrounded by magnetite. Structural analyses of the samples show 4 nm silver nanoparticles wrapped within compact cubic external structures of Fe oxide, with curious rectangular shape. The magnetic properties indicate a near superparamagnetic like behavior with a weak hysteresis at room temperature. The value of the anisotropy involved makes these particles candidates to potential applications in nanomedicine.

See the paper in Scientific Reports

Oct 10

Opinion article published at Jornal Público, de Portugal, 10/08/2014.

Opinion article published at Jornal Público, de Portugal, 10/08/2014.

See the complete article here.